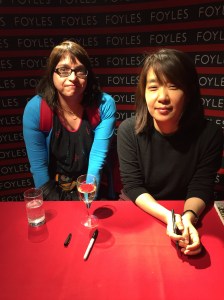

I will always remember where I was when I found out that writer Han Kang had been the recipient of the 2024 Nobel Literature prize. It was Thursday evening and I had gone with my mother to Sainsburys. I decided to check notifications on my phone and found I had been tagged in a post on Instagram. It was a picture of me and the writer that had been taken 8 years ago on the eve of the announcement of the 2016 Booker International. The Nobel foundation via its social media channels had chosen this amongst a few others to announce the writer’s significant win. A friend of mine had seen this, posted it in her stories and tagged me.

I let out a scream and rushed over to my mother and shouted, ‘Oh my god- Han Kang has just won the Nobel prize – this is amazing!’

Ever since 2007, I had been interested in Korean literature and its translations. I was introduced to the country courtesy of my friend and as an avid reader, always knew the best way to get to know a culture is through its literature. Having witnessed the steady rise of translations and different types of genres emerging, I knew how impactful this award meant, not just to Han Kang, but to fellow writers, translators, those involved in the publishing industry and the literature in South Korea overall.

I had first met Han Kang in 2014 with Deborah Smith. It was at the London Book Fair. It was also the year I began my Honorary Reporter duties for Korea.Net. I wanted to capture my love for Korean culture in some way and thought this outlet suitable. South Korean literature was the market focus that year and the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, or KTLI, had flown over 10 authors to the UK including Han. Kyoung Sook Shin, Hwang Sok-Yang, Yi Mun-yol, Hwang Sunmi, Kim Young-Ha to name a few.

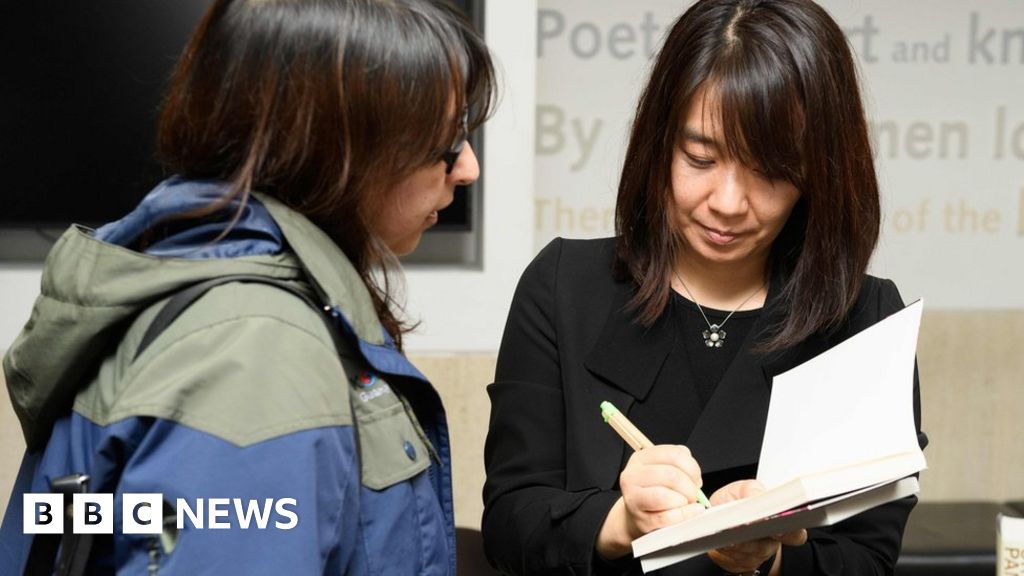

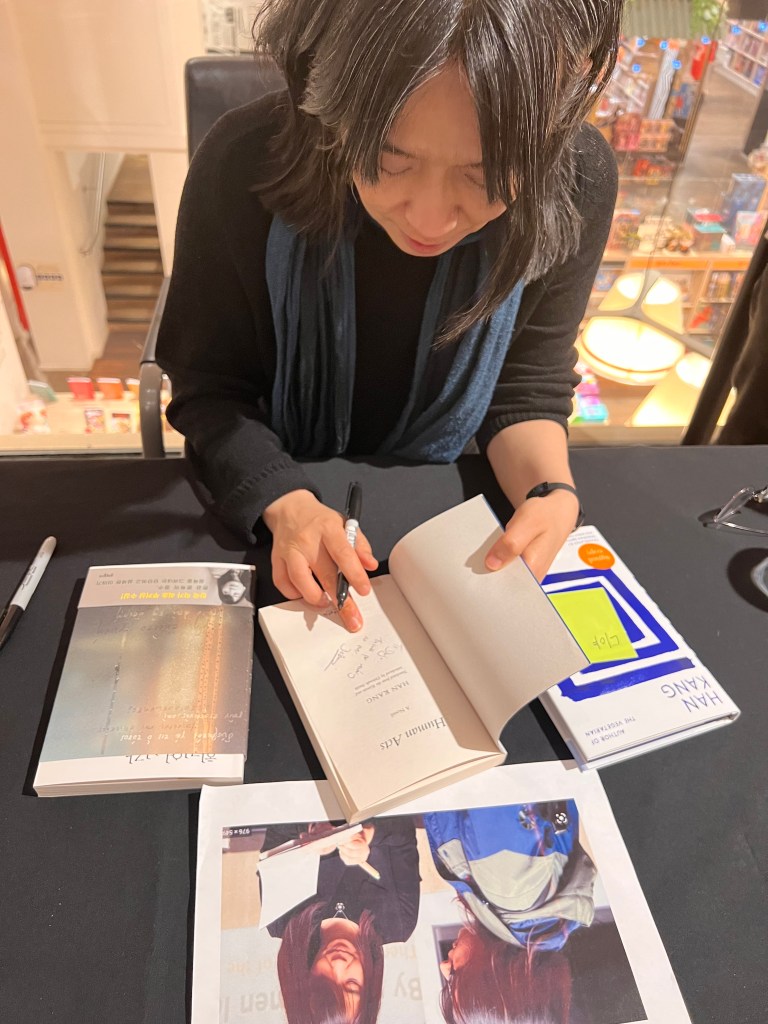

The picture with me and Han captured by Leon Neal, AFP Getty images, was the result of the decision I had made, in the surrounding of the British Library, to go up to Han to request her to autograph for my copy of the triptych novel ‘The Vegetarian.’ It was moments before both Smith and Han were due to go up on stage to talk about the translation and it was a day before they would find out they would win the International Booker prize. An award where equal prize money is awarded to both the author and the translator.

The novel was awarded the prize due to its ‘uncanny blend of beauty and horror’ as quoted by the judges.

In 2018, while visiting Korea for a wedding, I was invited to a book club run by translator Brother Anthony, where novels are read in both Korean and English translations. That month, Han Kang’s The White Book was discussed. I vividly recall a Korean man attending with annotated photocopies of The Vegetarian highlighting what he saw as many mistranslations by Deborah Smith. He handed this to translator Sophie Bowman asking they be passed on to Smith. I remember feeling sad and horrified. Nevertheless, it was a controversy at the time that did grip the nation.

Media outlets after celebrating the win, had reported on the mistranslated words, deletions of certain paragraphs in the text and exaggerated passages in the English novel. Charse Yun a visiting professor and teacher of translation, reflected on ‘Smiths ‘brilliant, yet flawed translation’ in his article in the LA times.

Yun argues, that whilst there are words that have been mistranslated , that do little to derail plot, the larger issues are the stylistic changes that Smith took with the novel and that alter the original text. Han has a particular minimalist, understated tone making the translation feel different. Although Yun praises the translation as a remarkable achievement as their are far more positives, given it was Smith’s first published translated work.

In her article for the Los Angeles Review of Books, Smith reflects on the backlash she faced and her subsequent collaboration with Han to correct future copies of the translations. She encourages and welcomes criticism of translations. Although she stresses on the importance of recognising how differing translations norms across countries and contexts can influence individual approaches. She asserts that she has not betrayed Han’s work;and Han herself, having read the translation, appreciated that it maintained her tone. While Smith may have changed the style of language, it was Han’s use of imagery, the novel’s three-part structure, and its climactic ending that garnered critical acclaim.

Sara Danius, a graduate and Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy that gives out the Nobel Prize, talked about the criteria of winning an award in Literature. In an article by Duke Today, she says, you are awarded not for a single piece of work, but for a life’s work that show’s something new with regards to content and form. ‘The Nobel Prize in Literature is awarded to someone who has done outstanding work in an idealistic direction that adds the greatest benefit to humankind.’

Han is the second South Korean to win a Nobel. The first was president Kim DaeJung in 2000, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his ‘Sunshine Policy’ towards North Korea. Han is the 18th woman to be awarded the prize in literature but 121st overall.

When selecting Han as the winner, the Nobel committee praised her for works. ‘intense poetic prose that confronts historical traumas and exposes the fragility of life.’

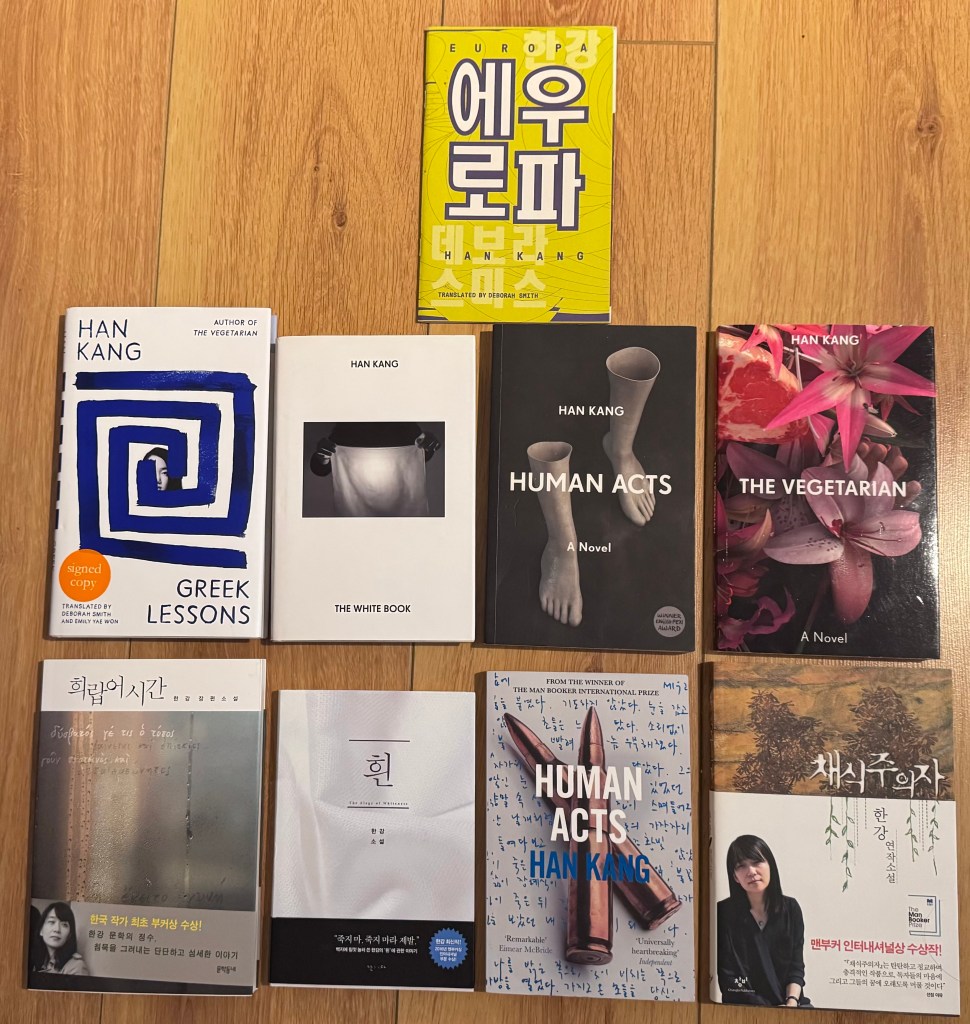

If it had not been for Smith’s love and admiration for wanting to translate the novel The Vegetarian, we may never have come to know of Han and her subsequent works. Human Acts, Greek Lessons, Utopia, and the forthcoming novel translated by Paige Aniyah Morris and Emily Yae Won, ‘We Do Not Part.’ We owe a lot of thanks to and gratitude to Smith, who co-translated Greek Lessons with Emily Yae Won. In reading of Han’s works, Human Acts is my most favourite works as it reflect’s Han’s style of tragic and heartfelt prose. Something I would advise against reading on public transport.

53 year old, Han, upon being awarded, was surprised and very honoured, but later declined to hold any press conference or celebratory occasion saying that it would be hard to celebrate whilst witnessing tragic events of the war. In an interview with the Nobel committee, Han wanted to drink tea and celebrate quietly with her son.

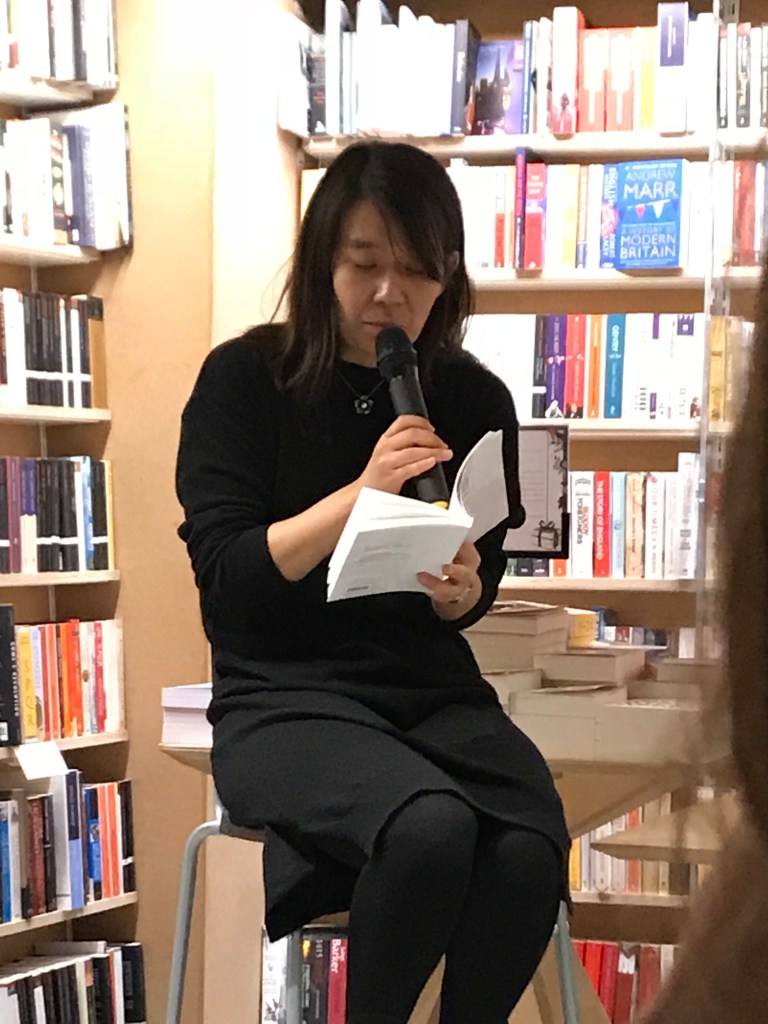

When Han speaks, for me, it’s like time slows down around her and every focus and emphasis is given to each word she utters. There is this intensity about human emotion and reaction and I feel this comes through in her novels.

The following day, after the winner of the Nobel prize had been announced, I was asked by the Korean Cultural Centre UK to provide them with a quote about Hang becoming a Nobel laureate. They were providing a press briefing to South Korea and were using the AFP Getty photo alongside.

I was overjoyed to find out that Han Kang was the recipient of this prestigious award. Han Kang is a writer of great compassion focusing on the fragility of human life. I have followed Korean translated literature ever since 2007 and I’m so proud to see it on the rise with genres, such as k- healing gaining popularity across the world.

All photos here are the authors, except the front page image courtesy of Leon Neal AFP via Getty images.